Just quit

Quitting projects in science is hard, but we should be doing a lot more of it.

We spend a lot of time as scientists thinking about how to choose a project—and that is, of course, critically important to success. But… no matter how carefully you try to pick out the most groundbreaking, innovative project imaginable, the simple truth is that not every project is going to be awesome. Consequently, just as important as the skill of choosing a project is the skill of knowing when to quit a project.

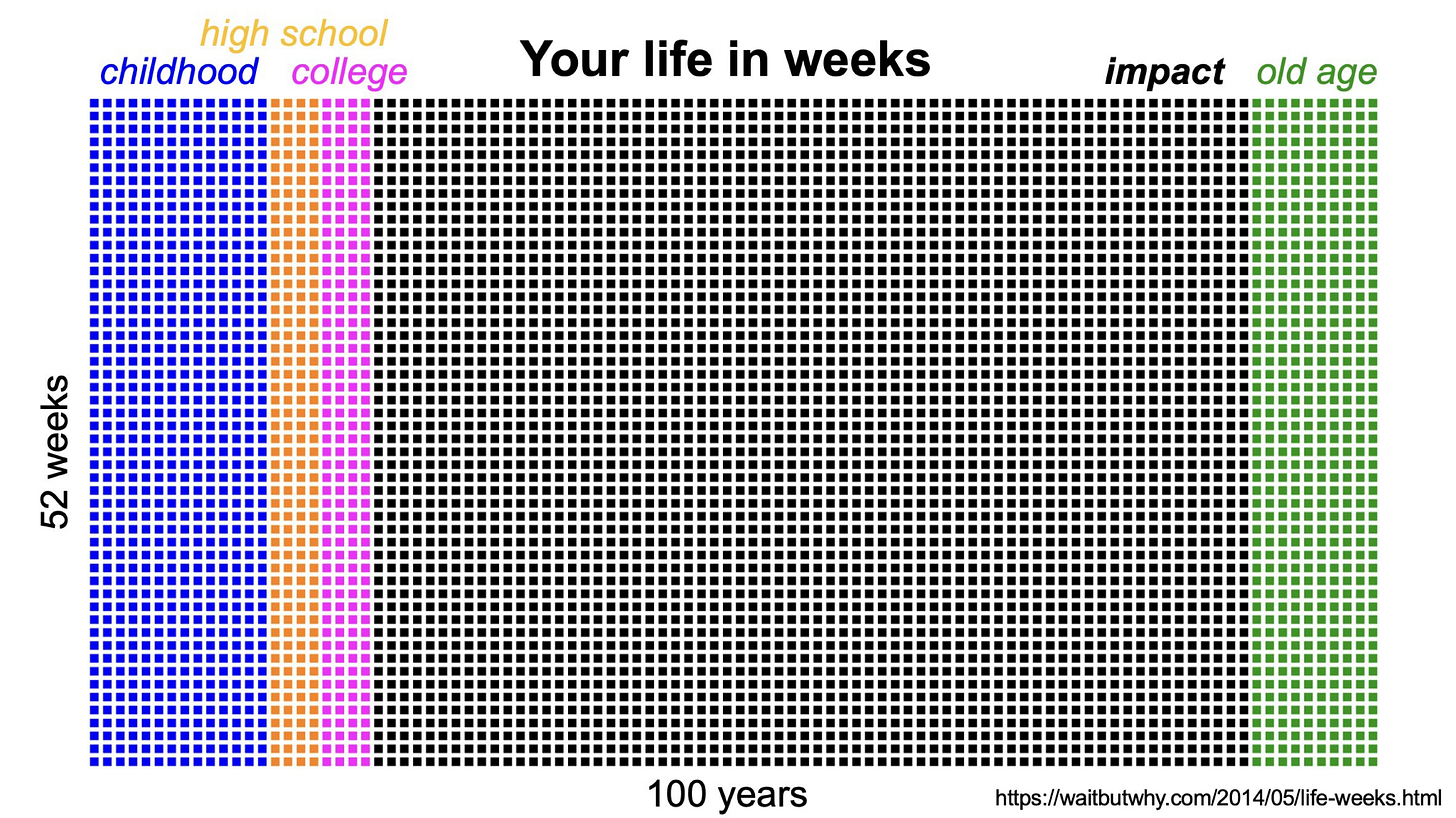

In my view, we should quit far more often than we do, for the simple reason that time is so very precious. Here is possibly the scariest diagram of all time:

That is not a lot of weeks. Each scientific project can take up 2-4 ENTIRE COLUMNS. As mentioned, the success of a project is way more probabilistic than we care to admit. So you have to sample, and that means rejecting many samples. Do not let this precious time go to waste. Sometimes, you just have to quit.

Why is it so hard to quit in science? Here are a few top reasons, all of which are based on fear:

Fear of the unknown. It’s in many ways easier to keep going with the devil you know.

Sunk cost fallacy. Don’t finish bad projects. A project typically takes 2-10x as long to finish as you think (and that’s even when you’ve already factored in the 2-10x). Do you really want to “just tie up a few loose ends” on a crummy project for the additional years required?

Falsely estimating the value of future and past time. People often worry about how long a new project will take. Let me tell you, finishing a project you don’t like will usually take way longer than one you do like. Also, time as you become more trained is worth much more than untrained time, especially for graduate students, so don’t waste precious time in the future on ill-spent time in the past.

Bad advice. Beware: other people typically value your time far less than you do. That’s not necessarily bad mentoring or anything sinister, just a very human reality. “Sure, do that extra control to kill the project”—sounds reasonable, and maybe it is, but it’s a lot easier to say when it costs very little to whoever says it.

Feeling like a quitter. We have been socialized in science to have a certain “stick-to-it-iveness” that I think is often counterproductive.

What can you do to make quitting easier?

Frame quitting by time, not results. It is practically a mantra in scientific management to say “I don’t care about time, I care about results”, and we pride ourselves on making decisions based on data. The problem is that there’s always “one more experiment” to do to see whether something will (or most likely, will not) work. Why spend time trying to do the experiment to kill a project you hate when you can just… stop working on it? Set a time, perhaps a week or a month or six months in the future, evaluate then based on whether you’re really getting where you imagined, and move on.

Do the control you’re scared of. Often, you know the go/no-go experiment you should do, but you put it off because you’re scared of the result. You know what I’m talking about. Just have to do it. Don’t chase wishy-washy results down the rabbit hole. When things work, they work. When they seem to maybe work, they usually don’t actually work.

Get some honest external feedback. Find someone that you really trust to give you honest feedback and ask them whether the project is worth pursuing. Sometimes, getting that negative signal from the outside is far more convincing than from your advisor/trainee.

Imagine the future of the project. Envision the title/abstract of the paper you imagine writing. Is that something you really want to spend potentially years writing the rest of? Often, people begin with a starter project in the lab, which can have a habit of turning into way more than a starter. If you’re just not that into it, quit.

And finally, just listen to that voice in your head. You probably already know you should quit, so just do it. I have quit projects many times in my career—grad school, postdoc, professor—and while the alternative is unknowable, with hindsight, it certainly feels like those were almost invariably the right decisions to make.

That life diagram is quite optimistic. To be working till 90, and death at age 100 is optimistic too. 78ish the the gender averaged current life expectancy in the US. For PhD studies take another 4 to 7 years off the impact part too. But your point is very well made.